A Taste of My Own Medicine

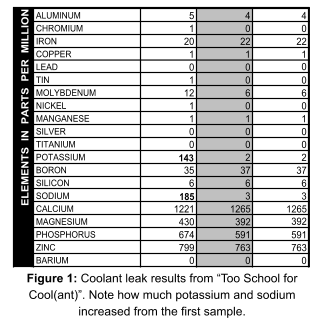

One of the things that oil analysis is really good at is finding antifreeze contamination. We use the spectral examination to identify antifreeze by looking at the elements potassium and sodium. Both of those elements can have harmless sources like additives, so it can sometimes be hard to spot low levels of antifreeze contamination. Still, if you know your oil doesn’t contain sodium and you aren’t using any after-market additives, when potassium and sodium show up together, it’s a safe bet you’ve got a problem on your hands.

Degrees of antifreeze

Of course, there are varying degrees of problems. When antifreeze contamination is mild, it doesn’t hurt anything. In fact, if the leak is steady, then it’s often something you can live with for years before you have to do anything about it, other than make sure you don’t run out of coolant and overheat your engine. However, if the leak is major, it can easily destroy an engine if left unchecked. As a contaminant, it disrupts the lubrication quality of the oil and causes poor wear at the bearings. It can also cause an oil to sludge up, and in really bad cases, it can turn the oil into black-pudding.

Fortunately, we can see antifreeze at extremely low levels, so you typically have some time to figure out how to proceed. In some situations, it can be an easy fix. In Slick Talk Podcast #147 (“Too School for Cool(ant)”), Blackstone Joe discusses a report where we found antifreeze for a customer (see Figure 1) and he was able to track down the problem (a bad oil cooler) and was back on the road in no time. Of course, the problem can also be major like a bad head gasket or intake manifold and require a lot of time and money to fix.

My past antifreeze problems

Over the years, I’ve reported a lot of antifreeze problems to customers and have had a few myself. My first personal experience with it was with my future-wife’s first car, a 1994 Buick Skylark. This was a very nice car and treated her well; however, it also came equipped with the GM 3100 (3.1L) V-6.

That was a great engine overall – lots of power and got good gas mileage, but it also developed an intake manifold leak at 83,000 miles. After talking to a mechanic friend about it, I learned that those engines were known for bad intake manifold gaskets and they all develop antifreeze leaks. With that in mind, it would seem foolish to buy another one, but that’s what we did. My wife fell in love with a 1997 Pontiac Grand-Am for her second car. It also had the GM 3100 V-6 and also eventually developed an antifreeze seep.

My current antifreeze problem

That was over 20 years ago now and since then we’ve upgraded to a 2021 Mazda 3 for my wife. I was very comfortable with this purchase because Mazda tends to make really good engines. We see a lot of them and it’s rare to find any problems. And our new one had been problem-free up until January of 2025 when I first noticed a little potassium and sodium showing up in the oil. I didn’t do anything at first because the rest of the report was excellent and wear metals were not affected, so I just decided to check it again at the next oil change. We’ve been running the oil around 10,000 miles and I didn’t want to wait that long to get confirmation of the problem, so I pulled a sample without changing the oil back in March, and sure enough, antifreeze was still present.

With a 4-cylinder engine, the common sources for antifreeze are narrowed down to just the head-gasket and the internal chain-driven water pump. Unlike our first two vehicles that had this type of problem, our Mazda is still under warranty, so I had my wife call the dealership and let them know about the problem. During that call, the service manager was at first dismissive and asked if she had the oil tested by Blackstone Labs. She said yes but didn’t say her husband was the President because we wanted to see how they would handle the situation. I know dealerships can be dismissive of oil reports, but this one was a little different because this dealership had been sending in samples to us for years, so they know oil analysis works. In any case, my wife made an appointment to have the car looked at.

Testing for antifreeze

As you might expect when you come into a dealership with a problem that’s not outwardly obvious, they don’t really want to do much. They did what’s known as a block check, (AKA: cooling system pressure test) and it passed. That test involves removing the radiator cap and attaching a special hand-powered air pump that has a pressure gauge attached to it. You pump the pressure until it gets to a certain level and then see if the pressure holds. This test is good for finding large/obvious leaks, but can easily miss small ones like mine. I suspect that’s because my leak probably isn’t present when the engine is cold and only shows up when the engine is hot and all the parts have expanded. The dealership also noted that they took off the oil fill cap and didn’t see any evidence of a leak. That part surprised me because I believe they were looking for yellow sludge that sometimes shows up under the oil fill cap (see Figure 2).

That sludge is actually fuel vapor that has condensed and while it looks bad, it’s harmless and will disappear on its own. Maybe if my cap happened to have that sludge present, they would have fixed the engine, but since they couldn’t find anything wrong, they just charged us $172 for a diagnostic fee and sent us on our way. That was frustrating to say the least and made me feel bad for all the customers that I’ve told had antifreeze leaks over the years, and likely got the same treatment at their dealership.

Dealer’s Choice

There was one interesting thing the dealership did mention, and that was I had the wrong coolant in use. My first thought was that’s impossible, the cooling system hadn’t been touched since it came out of the factory so the dealership must be wrong, but then I remembered the wreck. In July of 2024, my daughter had just gotten her learner’s permit and was getting practice driving the car when she went off the road (at slow speed) and hit a telephone pole (see Figure 3).

My wife called me and I came out and drove the car to a body shop to get repaired. While the damage looked minimal on the surface, it did damage a radiator mount, so when the repair shop fixed that they must have put the wrong coolant back in. With that incident in mind, I started to wonder if the collision itself could have somehow caused the antifreeze leak, or maybe just the fact that the wrong coolant was added, did it? I decided it would be fruitless to try and get Mazda to pay for the repair and I didn’t want to go back to the repair shop because it had been over a year since they fixed the damage.

What’s next?

So now I’m stuck with an engine that is leaking coolant into the oil and that will have to be addressed at some point. One of the things we tell our customers to do when antifreeze is found it to watch your coolant level, though that’s not quite as easy as it sounds. The car has a coolant overflow tank that is easy to look at, but how do you know if it’s dropping or not? I thought about marking on the bottle with a Sharpie, but I didn’t want anything permanent on there, so I went with masking tape (see Figure 4). After a few months, it did start to look like I was losing coolant, but I wasn’t completely sure. You see, the coolant level changes in that bottle depending on if the coolant is hot or cold and I don’t know if I put the tape on the bottle when it was hot or cold, so my first try at visually monitoring the coolant level was inconclusive. Next time, I will write on the masking tape if the coolant was hot or cold, so I can eliminate that variable.

I’m not sure how this will all turn out yet. I might have to get out the tools and crack the engine open, or maybe I can keep the oil changes short and limp along until we decide to get another car. I’ll keep you informed.