Fuel in Diesels

For our last newsletter, we did an experiment where we actually tried to get fuel dilution to show up in the oil. Amanda’s Kia was our guinea pig, and she tried hard to get some fuel to show up but had very little success. She tried idling for ten minutes and she tried lots of city driving, but could hardly get anything more than a trace or so. Maybe that’s just a testament to Kia and their fuel system engineering, or maybe she was just unlucky. It’s hard to say. However, fuel dilution does show up for a lot of our customers and after the last newsletter, we received some e-mails asking for more information about fuel, especially in diesel engines with possible fuel dilution problems.

A little history

Diesel engines started showing up in pickup trucks back in the 1980s and while those engines didn’t particularly wear well, fuel dilution wasn’t really a big issue.

In the 1990s, these engines really started coming into their own. Wear metals improved and the oil changes started getting longer and longer. Ford started using the Navistar 7.3L Power Stroke and Dodge used the Cummins 6BT 5.9L, and both were excellent engines. They produced a lot of power and left very little metal in the oil to show for it.

GM used the Detroit Diesel 6.5L, and while that was a good engine and a lot of them are still on the road today, it tended to make a lot more metal than its competitors. It wasn’t until GM started the Isuzu 6.6L Duramax that it really had a world- class diesel that was every bit as good as what Ford and Dodge were using.

With this new generation of engines, we started seeing people run 5,000-mile oil changes regularly, where the old standard was just 3,000 miles. And oil changes have gotten longer and longer since.

These days it’s not uncommon at all to see those engines running 10,000 miles on the oil without any special oil filtration set-up. Of course, a lot of that is dictated by the type of use they see. This was also the carefree days before emission controls starting becoming mandatory.

For some of you, the words emission controls may make you turn away in disgust and I’ll admit, on my own truck engine (a gasoline powered GM 350), the emission controls haven’t gotten the attention the rest of the engine has. But really the idea isn’t really all that bad.

Piston powered aircraft engines don’t have any emission controls on them, but those engines are plagued by rust and corrosion because condensation from the air is allowed to enter through the breather. Modern gasoline and diesel engines don’t have that problem because their crankcases are sealed to the elements and that keeps corrosion to a bare minimum. It’s also one of the reasons you don’t really need to change your oil on a time basis anymore. We get a lot of questions about if an oil will last a year or not and the answer is almost always yes, because very little corrosion builds up on these engines.

Of course, gasoline-powered engines have had emission control systems on them since the 1970s and that means the engine designers have had a lot of time to get it right. When emission controls started appearing on diesel engines in 2005 and 2006, there were a lot of growing pains with that introduction. Couple that with the fact that competition brought about the need for more and more power, and now we started seeing changes in the oil samples, mainly at fuel dilution.

We first started seeing a lot of fuel when Navistar came out with the 6.0L Power Stroke in 2003. Those engines almost always had a lot of fuel in the oil, especially when they were new¾and when I talk about a lot, I mean 4% and 5%.

We weren’t sure exactly what cased this, but it was showing up in almost every sample we saw and this presented a problem for us because we had always considered 2.0% to be an “action” level of fuel. So what do you do when every engine starts showing more than 2.0% fuel? Do you start sending every owner back to the dealer saying there’s a problem? And what do you do if you see a lot of fuel dilution, but wear metals continue to look good?

So the 6.0L Power Stroke caused us to take a different look at fuel and how much of a concern it really is. No longer could we consider 2.0% is a major problem. Now we suggest that it’s only an issue if the oil level is rising on your dipstick, or if the amount of fuel we find in each sample is increasing. As it turns out, continual fuel dilution in the oil at around 2.0% to 3.0% sometimes is from a problem, but it should not be considered a major one and I know about that first-hand.

About my Passat

In 2004 my wife and I bought a Volkswagen Passat with the 1.8L turbo gasoline engine. Almost from the start, this engine was leaving a lot of fuel in the oil and I would look at the analysis results and just shrug my shoulders. The engine was running fine and wear metals were acceptable, but the fuel mileage was never quite a good as advertised. For me, that didn’t seem like a good enough reason to tear into the fuel system.

Shortly after we bought the Passat, Volkswagen set us a letter saying they would extend the engine warranty to 10 years or 100,000 miles due to sludging problems they were having. I suspected these problems stemmed from a lot of fuel dilution in the oil coupled with really long oil runs, but I’m not sure. The kicker for the extend warranty was I had to change oil every 5,000 miles and I had to use a VW-approved oil. Of course, they approved expensive oils like Elf and Total, and those aren’t on my approved list. My list includes oils that are on sale at Wal-Mart, so I decided to stick with my oils and just change the oil at 3,000 miles. So far the plan has worked but if it fails, I’ll be writing about how I rebuilt the engine myself (twice) in my Dad’s barn.

In the end, we haven’t done anything about the continual fuel in our Passat’s oil (except curse VW), but the engine is still running fine and is close to the magic 100,000-mile mark. When we hit 100K, we’ll unload it and get my wife the new car of her dreams (a white Jaguar S-type). So despite the fuel being present in every report, really the only problem this has caused is our MPG isn’t quite what it should be.

Back to diesel engines

So anyway, the fuel dilution problems in the 6.0L Power Stroke eventually got better and those engines now look as good as any we see, so they’ve changed something to solve the fuel problem.

Then came the next generation of diesels (the 6.4L Power Stroke) and the fuel problems started up again. It’s not uncommon to sees excess fuel in over 2% of the small diesel engine samples we see today, and when it shows up that often, it’s hard to say it’s a major issue. It shouldn’t really be there, but it doesn’t necessarily warrant a trip to the dealer either.

The source of the fuel dilution differs from one engine manufacturer to the next, though injectors and emission control systems appear to be the root cause of most of these problems.

For the new 6.4L Power Strokes, if it’s not an injector it could be another part of the fuel system, like a pump. The DPF (diesel particulate filter) regeneration process will also cause fuel to show up in the oil. Does that mean these new engines are junk? Not at all. It just shows they have some growing pains to work out and once that happens, the fuel dilution problems will eventually taper off.

Until then, don’t get too excited 2.0% or more of fuel dilution, but do watch for an increased oil level on your dipstick. While you may think an engine that makes oil is like the goose that laid the golden egg, it’s really a possible sign of problems down the road. Small amounts of fuel are okay, but if the oil level is rising or if we’re seeing more and more fuel in each sample you do, fuel could be a problem.

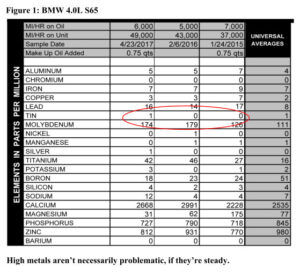

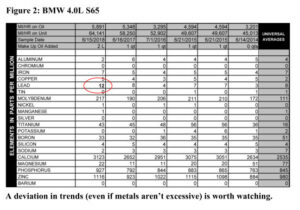

If you have them, trends are the most helpful thing we look at in determining your engine’s health. It takes three samples to get a good trend going (though we can often tell if something is amiss earlier than that).

If you have them, trends are the most helpful thing we look at in determining your engine’s health. It takes three samples to get a good trend going (though we can often tell if something is amiss earlier than that).

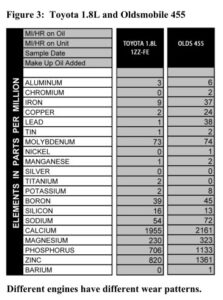

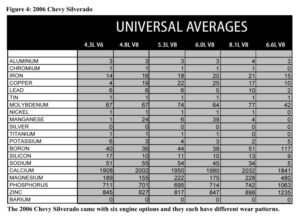

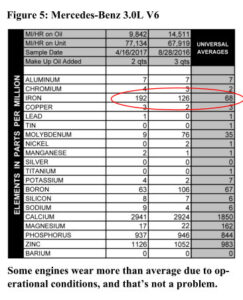

If we don’t know what kind of engine you have, we might end up comparing your numbers to the wrong set of averages, or just a generic engine file. We can still tell if something is way out of line, but the more subtle differences between your engine and averages are harder to see.

If we don’t know what kind of engine you have, we might end up comparing your numbers to the wrong set of averages, or just a generic engine file. We can still tell if something is way out of line, but the more subtle differences between your engine and averages are harder to see.

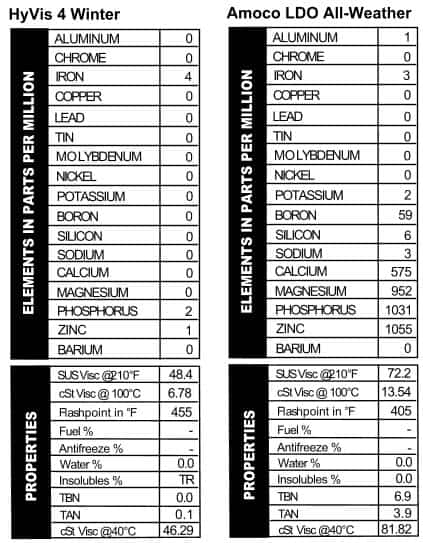

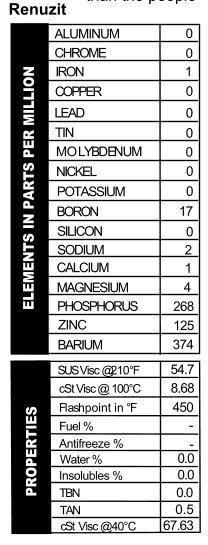

HyVis 4 Winter

HyVis 4 Winter additive in it, just not any that we read. The grade is not listed on the can, but the viscosity came back as a light 20W. With the lack of additive it’s not surprising that the TBN read 0.0. It’s tempting to do an experiment and run this apparent mineral oil for 10,000 miles in the dead of winter, just to see what would happen. If you know of any guinea pigs, send them our way!

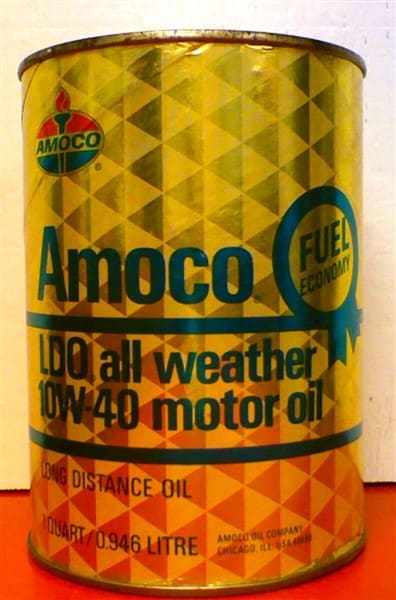

additive in it, just not any that we read. The grade is not listed on the can, but the viscosity came back as a light 20W. With the lack of additive it’s not surprising that the TBN read 0.0. It’s tempting to do an experiment and run this apparent mineral oil for 10,000 miles in the dead of winter, just to see what would happen. If you know of any guinea pigs, send them our way! the country, and I’ll always associate the blue, red, and white logo with long trips across the country in our green van with the velour bed and hanging beads. But Amoco did more than fill up gas tanks in the 70s–they also sold oil, and this “Long Distance” version is an SAE 10W/40. The additive package looks a lot like the Mobil Special oil we saw: heavy on phosphorus and zinc, lighter on calcium and magnesium (Figure 2). Just the right oil for a couple of bandana-wearing hippies traveling with two little kids from Indiana to Nova Scotia in 1976 in a green van with a sunset painted on the side. Ah, the ’70s.

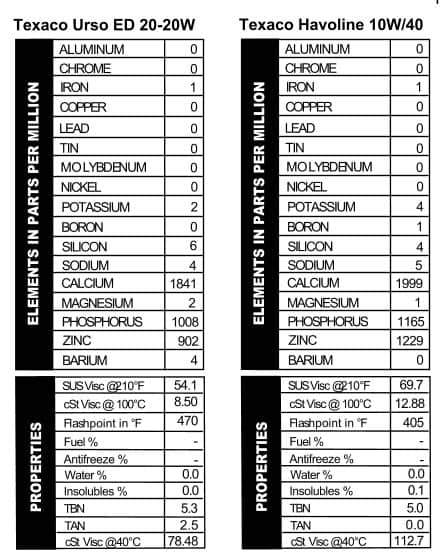

the country, and I’ll always associate the blue, red, and white logo with long trips across the country in our green van with the velour bed and hanging beads. But Amoco did more than fill up gas tanks in the 70s–they also sold oil, and this “Long Distance” version is an SAE 10W/40. The additive package looks a lot like the Mobil Special oil we saw: heavy on phosphorus and zinc, lighter on calcium and magnesium (Figure 2). Just the right oil for a couple of bandana-wearing hippies traveling with two little kids from Indiana to Nova Scotia in 1976 in a green van with a sunset painted on the side. Ah, the ’70s. The viscosity read like what we see today out of a standard 5W/30. Texaco Havoline Super Premium 10W/40, on the other hand, looks a lot like one of today’s diesel-use oils in additives (Figure 4), with a normal 10W/40 viscosity.

The viscosity read like what we see today out of a standard 5W/30. Texaco Havoline Super Premium 10W/40, on the other hand, looks a lot like one of today’s diesel-use oils in additives (Figure 4), with a normal 10W/40 viscosity.

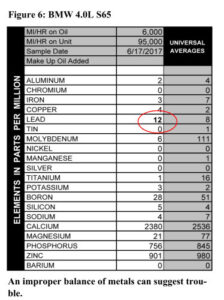

only did they not make multi-viscosity oils that long ago, but the can comes from zip code 90017 so it has to be from 1963 or later. According to the can, it’s 100% parrafinic oil with selected additives, which our spectrometer reveals to be your standard line-up of calcium, phosphorus, and zinc (Figure 6). Look at that viscosity though¾it’s higher than we see in today’s 20W/50s.

only did they not make multi-viscosity oils that long ago, but the can comes from zip code 90017 so it has to be from 1963 or later. According to the can, it’s 100% parrafinic oil with selected additives, which our spectrometer reveals to be your standard line-up of calcium, phosphorus, and zinc (Figure 6). Look at that viscosity though¾it’s higher than we see in today’s 20W/50s.

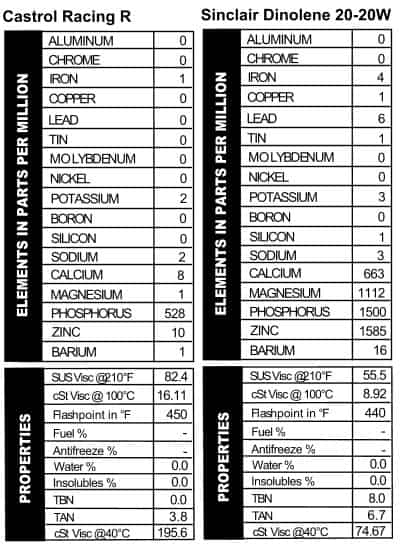

Like modern oils, they stress the high quality of the oil with terms like “organo-metallic” that are meant impress those of us who aren’t in the oil business. I don’t know if I’d call this a masterpiece in oil work though: it looks like what we see out of ATFs these days as far as additives go (mostly phosphorus with a little zinc thrown in). Since the word “Racing” is stamped into the top of the can, the thick viscosity (like a 50W) makes sense (Figure 7).

Like modern oils, they stress the high quality of the oil with terms like “organo-metallic” that are meant impress those of us who aren’t in the oil business. I don’t know if I’d call this a masterpiece in oil work though: it looks like what we see out of ATFs these days as far as additives go (mostly phosphorus with a little zinc thrown in). Since the word “Racing” is stamped into the top of the can, the thick viscosity (like a 50W) makes sense (Figure 7). I’ve always had a soft spot in my heart for Sinclair. The can has a picture of a dinosaur on it! This shit came from the ground, no doubt about it! Another 20-20W oil, the oil is light on advertising copy but heavy on additives. In fact, it looks a lot like recent versions of Shell’s Rotella 5W/40, except with a little less calcium. It’s much lighter than Shell’s 5W/40, though, with a viscosity reading like a 30W or a heavy 20W oil. Note the presence of lead (Figure 8).

I’ve always had a soft spot in my heart for Sinclair. The can has a picture of a dinosaur on it! This shit came from the ground, no doubt about it! Another 20-20W oil, the oil is light on advertising copy but heavy on additives. In fact, it looks a lot like recent versions of Shell’s Rotella 5W/40, except with a little less calcium. It’s much lighter than Shell’s 5W/40, though, with a viscosity reading like a 30W or a heavy 20W oil. Note the presence of lead (Figure 8).

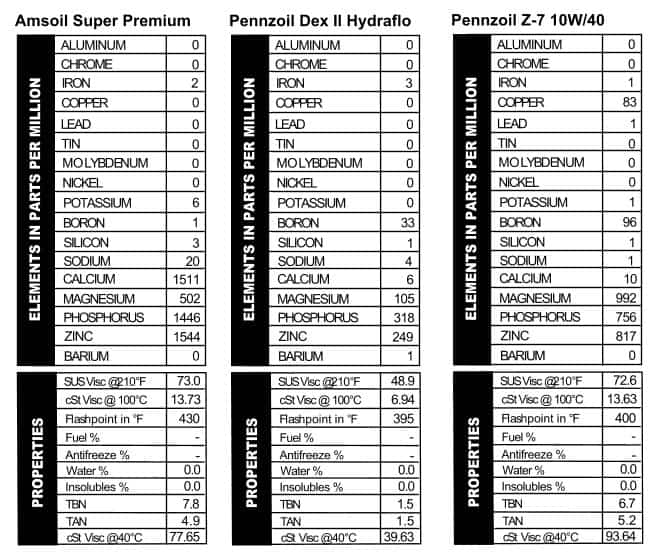

Modern Amsoil products tend to be heavy on additives and that was true back in the day as well (Figure 9). Just for fun, we compared this oil with a virgin sample of Amsoil 10W/40 that we ran in February 2012 and they look a lot alike. The only difference is in the older oil there’s less of everything: 500 ppm less calcium, and 100-200 ppm less phosphorus and zinc. They used magnesium in the older oil, while the TBN and viscosities were nearly identical.

Modern Amsoil products tend to be heavy on additives and that was true back in the day as well (Figure 9). Just for fun, we compared this oil with a virgin sample of Amsoil 10W/40 that we ran in February 2012 and they look a lot alike. The only difference is in the older oil there’s less of everything: 500 ppm less calcium, and 100-200 ppm less phosphorus and zinc. They used magnesium in the older oil, while the TBN and viscosities were nearly identical. over these two old cans. Originally, Penn’s Oil came from an oil field in Pennsylvania and was christened with a Liberty Bell logo to remind users of its Pennsylvania roots. This can of ATF clearly has an earlier generation of logo on it, and Google informs me that Dexron II was introduced in 1972. This may very well have been the transmission oil that kept our green van chugging through the ’70s. There are a lot of different ATFs in stores today, though generally they have about the same additive configurations. This one is a little different in that it has more boron, magnesium, and zinc than most modern ATFs. The viscosity is right where we’d expect it to be though. Pennzoil’s 10W/40 oil can is flashy, a la the

over these two old cans. Originally, Penn’s Oil came from an oil field in Pennsylvania and was christened with a Liberty Bell logo to remind users of its Pennsylvania roots. This can of ATF clearly has an earlier generation of logo on it, and Google informs me that Dexron II was introduced in 1972. This may very well have been the transmission oil that kept our green van chugging through the ’70s. There are a lot of different ATFs in stores today, though generally they have about the same additive configurations. This one is a little different in that it has more boron, magnesium, and zinc than most modern ATFs. The viscosity is right where we’d expect it to be though. Pennzoil’s 10W/40 oil can is flashy, a la the  1980s. It’s “The Motor Oil With Z-7” and although they don’t specify what that is, they do specify that “You need no extra oil additive.” So that’s reassuring. It’s rated SF-SC-CC, so I’d place it at about 25 years old. Maybe the magic of Z-7 is copper: that’s something we saw a lot of back in the day, when Blackstone was founded. Interestingly, magnesium is the dominant additive in this one, followed by zinc, phosphorus, copper, and boron (Figure 10). The flashpoint was lower than what we see today from 10W/40s.

1980s. It’s “The Motor Oil With Z-7” and although they don’t specify what that is, they do specify that “You need no extra oil additive.” So that’s reassuring. It’s rated SF-SC-CC, so I’d place it at about 25 years old. Maybe the magic of Z-7 is copper: that’s something we saw a lot of back in the day, when Blackstone was founded. Interestingly, magnesium is the dominant additive in this one, followed by zinc, phosphorus, copper, and boron (Figure 10). The flashpoint was lower than what we see today from 10W/40s.

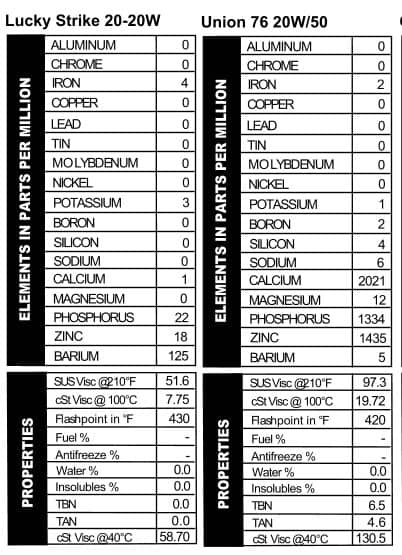

a can like the others. This one was sold in a 5-quart metal jug. I particularly love this one, because the can not only says you’ll “Cut Your Oil Bills In Half,” but the first point of advertising on the side is a “Faster Getaway!” Now, they don’t actually say that this is the choice of oils for bank robbers, but I know if it was 1941 and my hungry Great Depression self was contemplating which oil to put in my Ford Special for bank-robbing time, this is the oil I’d pick. With practically no calcium or magnesium present, the oil’s TBN read 0.0, but it does provide would-be crooks with phosphorus, zinc, and barium as well as a 20W viscosity for the getaway (Figure 11). When you’re busy working a tommy gun, the last think you want to think about is whether or not you’ve made the right choice in oil.

a can like the others. This one was sold in a 5-quart metal jug. I particularly love this one, because the can not only says you’ll “Cut Your Oil Bills In Half,” but the first point of advertising on the side is a “Faster Getaway!” Now, they don’t actually say that this is the choice of oils for bank robbers, but I know if it was 1941 and my hungry Great Depression self was contemplating which oil to put in my Ford Special for bank-robbing time, this is the oil I’d pick. With practically no calcium or magnesium present, the oil’s TBN read 0.0, but it does provide would-be crooks with phosphorus, zinc, and barium as well as a 20W viscosity for the getaway (Figure 11). When you’re busy working a tommy gun, the last think you want to think about is whether or not you’ve made the right choice in oil.

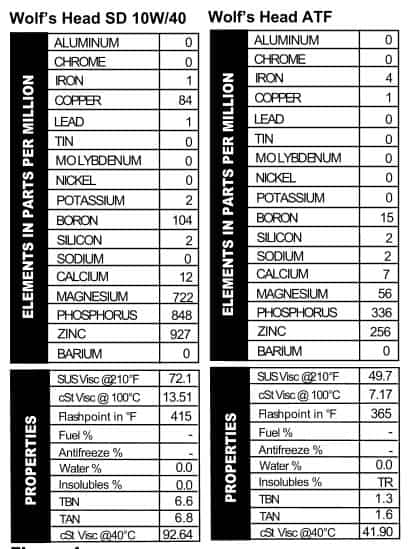

Wolf’s Head SD 10W/40

Wolf’s Head SD 10W/40 Wolf’s Head ATF

Wolf’s Head ATF white, and blue, so you can feel patriotic when you buy it (unless

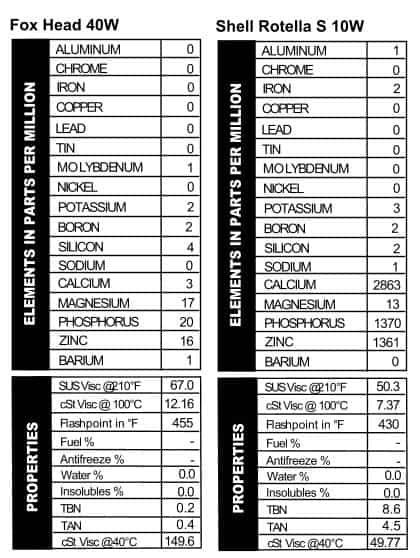

white, and blue, so you can feel patriotic when you buy it (unless  you’re in Canada. Then you can indulge in justified rage about Americans and how we think we’re the center of the world). Fox Head oil was made by the Tritex Petroleum company out of Brooklyn, NY, and my extensive research (aka first-page Google results) tells me the company still exists and is presently located in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The logo, a sly-looking fox, has nothing on today’s slick oil packages. And the oil itself also has nothing on today’s oils: the oil itself is nearly bereft of additives. Basically a mineral oil, it has a little magnesium, phosphorus, and zinc in it, and not a lot else (Figure 3). This is not necessarily a problem, however. As you’ll recall in the article when Ryan used 30W aircraft oil in his truck, wear went up a little but the engine didn’t fail or anything. Still, I won’t be putting it in my Outback anytime soon.

you’re in Canada. Then you can indulge in justified rage about Americans and how we think we’re the center of the world). Fox Head oil was made by the Tritex Petroleum company out of Brooklyn, NY, and my extensive research (aka first-page Google results) tells me the company still exists and is presently located in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The logo, a sly-looking fox, has nothing on today’s slick oil packages. And the oil itself also has nothing on today’s oils: the oil itself is nearly bereft of additives. Basically a mineral oil, it has a little magnesium, phosphorus, and zinc in it, and not a lot else (Figure 3). This is not necessarily a problem, however. As you’ll recall in the article when Ryan used 30W aircraft oil in his truck, wear went up a little but the engine didn’t fail or anything. Still, I won’t be putting it in my Outback anytime soon. long they’ve been making this oil and the guy not only could not tell me, but he was unable to tell me who might know. Surely someone at that company has a historical file? If so, they’re not sharing that info with plebeians like us. He did mention that Rotella really made its name in the ’70s, though I’m guessing this can of SF, SE, SC oil was made in the late ’80s. He also said the “S” versions of Rotella were sold internationally, and indeed, this can came from our friendly neighbors to the north (*waves hi to Canada). Suffice it to say that the oil has changed very little over the years. Its main additives are the same as what we see today, but the interesting part of this oil is that it’s a 10W (Figure 4). We often see heavy-duty thin-grade additive packages in tractor-hydraulic fluids, which are used in systems like transmissions and hydraulic systems in off-highway equipment like bulldozers and backhoes. Note the TBN of this oil read higher than most of the others we’re talking about. That’s because of the high calcium level¾the TBN is based on the level of calcium sulfinate and/or magnesium sulfinate. When those compounds aren’t present, you get a low TBN.

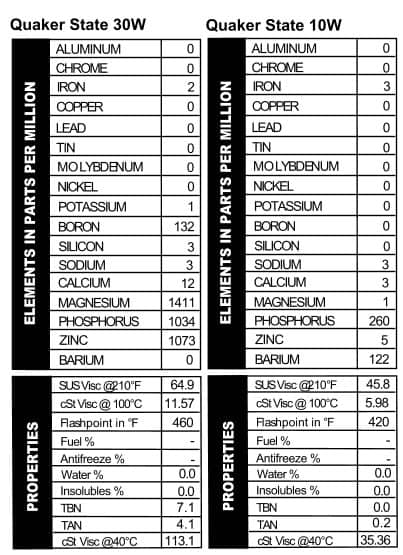

long they’ve been making this oil and the guy not only could not tell me, but he was unable to tell me who might know. Surely someone at that company has a historical file? If so, they’re not sharing that info with plebeians like us. He did mention that Rotella really made its name in the ’70s, though I’m guessing this can of SF, SE, SC oil was made in the late ’80s. He also said the “S” versions of Rotella were sold internationally, and indeed, this can came from our friendly neighbors to the north (*waves hi to Canada). Suffice it to say that the oil has changed very little over the years. Its main additives are the same as what we see today, but the interesting part of this oil is that it’s a 10W (Figure 4). We often see heavy-duty thin-grade additive packages in tractor-hydraulic fluids, which are used in systems like transmissions and hydraulic systems in off-highway equipment like bulldozers and backhoes. Note the TBN of this oil read higher than most of the others we’re talking about. That’s because of the high calcium level¾the TBN is based on the level of calcium sulfinate and/or magnesium sulfinate. When those compounds aren’t present, you get a low TBN. Quaker State 30W & 10W

Quaker State 30W & 10W

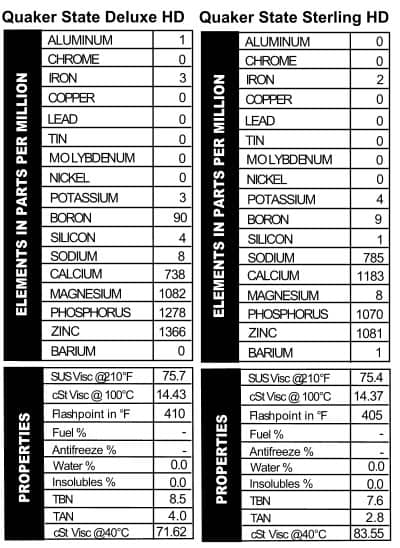

these oils are mostly the same; they’ll throw in a few slight differences in additives and call it good. These cans of Quaker State, however, were mostly pretty different. The Deluxe version looked a lot like their 30W oil (but more calcium–Figure 7). Quaker State Sterling HD 10W/40, on the other hand, went out on a limb with almost 800 ppm sodium, almost no magnesium, and then levels of calcium, phosphorus, and zinc that are comparable with today’s oils. Touted as “Energy Saving Motor Oil,” Quaker State was getting its game on in pushing this brand: it mentions “special friction modifying additives,” the longevity of the company (over 60 years when the can was made), and its suitability for those wishing to follow extended drain intervals. Heck, I’m sold, and I see this stuff all the time.

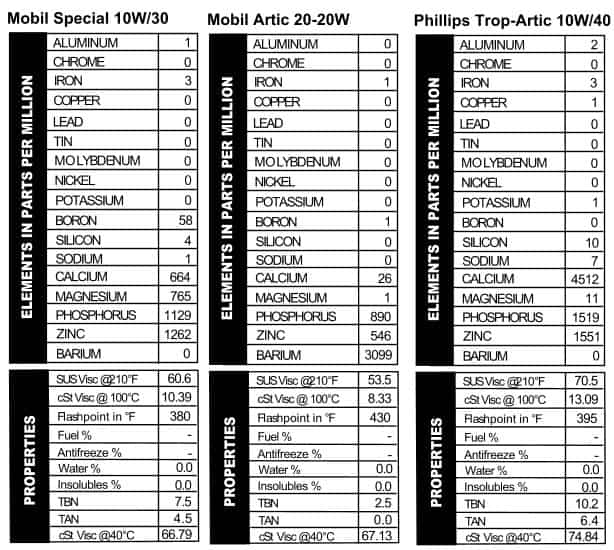

these oils are mostly the same; they’ll throw in a few slight differences in additives and call it good. These cans of Quaker State, however, were mostly pretty different. The Deluxe version looked a lot like their 30W oil (but more calcium–Figure 7). Quaker State Sterling HD 10W/40, on the other hand, went out on a limb with almost 800 ppm sodium, almost no magnesium, and then levels of calcium, phosphorus, and zinc that are comparable with today’s oils. Touted as “Energy Saving Motor Oil,” Quaker State was getting its game on in pushing this brand: it mentions “special friction modifying additives,” the longevity of the company (over 60 years when the can was made), and its suitability for those wishing to follow extended drain intervals. Heck, I’m sold, and I see this stuff all the time. Mobil is no slouch in the marketing department, but they really outdid themselves with the can we tested, “Mobil Special.” The name alone tells you all you need to know about why to buy this oil. All oil companies like to mess with their additive packages, and Mobil, like the others, changes their oil up fairly frequently. That was the case back in the day too, because the additive package in this “Special” oil is different from what we typically see in today’s oil. Apparently Mobil was an early rider on the ZDDP train, because this oil is chock-full of both phosphorus and zinc. Calcium and magnesium are present too, but at lower levels (Figure 8). We also tested a sample of Mobil Artic oil. The Artic

Mobil is no slouch in the marketing department, but they really outdid themselves with the can we tested, “Mobil Special.” The name alone tells you all you need to know about why to buy this oil. All oil companies like to mess with their additive packages, and Mobil, like the others, changes their oil up fairly frequently. That was the case back in the day too, because the additive package in this “Special” oil is different from what we typically see in today’s oil. Apparently Mobil was an early rider on the ZDDP train, because this oil is chock-full of both phosphorus and zinc. Calcium and magnesium are present too, but at lower levels (Figure 8). We also tested a sample of Mobil Artic oil. The Artic can is clearly older than the other Mobil can¾the logo is older, and there’s no zip code listed with the address, so it’s pre-1963. A straight 20W, it’s labeled as HD oil, meeting “Car Builders’ Most Severe Service Tests.” While it’s “Artic” and not “Arctic,” we can’t help thinking this oil is meant for cold-weather operation. The can even looks like it’s ready for winter: all white, but with a little color on it so you don’t lose it in the snow when you’re out in the tundra changing your oil. This one definitely has an unusual additive package, relying heavily on barium (maybe it’s got a purpose after all!). Interestingly, less zinc is present than phosphorus (Figure 9). Nowadays it’s the other way around.

can is clearly older than the other Mobil can¾the logo is older, and there’s no zip code listed with the address, so it’s pre-1963. A straight 20W, it’s labeled as HD oil, meeting “Car Builders’ Most Severe Service Tests.” While it’s “Artic” and not “Arctic,” we can’t help thinking this oil is meant for cold-weather operation. The can even looks like it’s ready for winter: all white, but with a little color on it so you don’t lose it in the snow when you’re out in the tundra changing your oil. This one definitely has an unusual additive package, relying heavily on barium (maybe it’s got a purpose after all!). Interestingly, less zinc is present than phosphorus (Figure 9). Nowadays it’s the other way around. see out of modern 15W/40s¾a stout additive package and a relatively thick viscosity (Figure 10). In other words, even though this oil is several decades old, it would be fine to use in your F150 tomorrow.

see out of modern 15W/40s¾a stout additive package and a relatively thick viscosity (Figure 10). In other words, even though this oil is several decades old, it would be fine to use in your F150 tomorrow.

and needed some oil for my Passat. It just starting to clatter a little on start up and when I checked the oil, it was down two quarts. The clatter sounded something like “Sell Me” in German.

and needed some oil for my Passat. It just starting to clatter a little on start up and when I checked the oil, it was down two quarts. The clatter sounded something like “Sell Me” in German.

One thing led to another and before I knew it I had bought 28 cans of old oil and spent almost $1,000. Pretty soon these oils started rolling in and I experienced a little buyers remorse. Did I really need to buy all this? What was I going to do with the cans? Once you open a can of oil, it’s almost impossible to seal up properly. Would there be anything to even see in these samples? And, does oil go bad? We get this last question all the time, and my answer has always been no, but I was dealing with oils from the 1930s,1940s, and 1950s here–really old stuff. Maybe all the additive in there (if any was even used) would settle out and there wouldn’t be anything for us to read. Fortunately, I had bought some oil that would help answer that.

One thing led to another and before I knew it I had bought 28 cans of old oil and spent almost $1,000. Pretty soon these oils started rolling in and I experienced a little buyers remorse. Did I really need to buy all this? What was I going to do with the cans? Once you open a can of oil, it’s almost impossible to seal up properly. Would there be anything to even see in these samples? And, does oil go bad? We get this last question all the time, and my answer has always been no, but I was dealing with oils from the 1930s,1940s, and 1950s here–really old stuff. Maybe all the additive in there (if any was even used) would settle out and there wouldn’t be anything for us to read. Fortunately, I had bought some oil that would help answer that.

However, that really didn’t get down to answering the question: Is this oil still good to use? For that, I was going to have to run another test.

However, that really didn’t get down to answering the question: Is this oil still good to use? For that, I was going to have to run another test. .

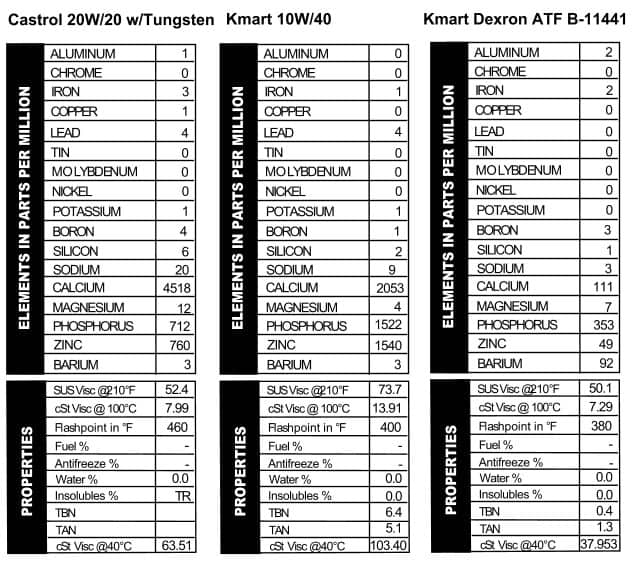

. Looking at the results, I’d say this oil is indeed deluxe. The viscosity is pretty strong for a 10W/40, and the additives would be suitable for diesel use. The oil does have a CC rating as well as an SE rating, and those put the date of this oil as being made sometime in the 1970s. The ATF has a standard additive package until you get down to barium. That’s not used much anymore. See figures 5 and 6 for the analyses.

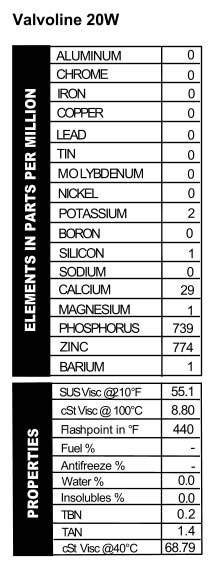

Looking at the results, I’d say this oil is indeed deluxe. The viscosity is pretty strong for a 10W/40, and the additives would be suitable for diesel use. The oil does have a CC rating as well as an SE rating, and those put the date of this oil as being made sometime in the 1970s. The ATF has a standard additive package until you get down to barium. That’s not used much anymore. See figures 5 and 6 for the analyses. Valvoline SAE 20W – API SB

Valvoline SAE 20W – API SB