Last month we got an email from John, who had some questions about his report. His F250 was showing traces of coolant in the oil, and lead, from bearings, was elevated. He had the engine out of the truck pending repairs and wanted to know: how much lead is too much? Did he need to replace the bearings?

“Do I need to worry?” is a common question, and one there’s not one easy answer for. We’ve had people pull the bearings out of a Corvette when lead was only a few ppm above average and we said in the report, “You don’t need to do anything about this yet.” (For the record, that guy called us and said his bearings looked fine and was kind of honked off about it.)

We’ve had people with metals that are high all along, but not changing, and it never turns into a problem. And we’ve had people not pursue what appeared to be a problem, and regret it in the end (this is especially problematic when the engine is in an airplane).

So how do we decide what’s a problem and what’s not? It would be great if there was a magic number, but there’s not. We assess each engine individually, mainly focusing on these things:

- How your sample compares to your trends

- How your sample compares to average

- The balance of metals to each other

- Whether you’re using additives

Trends

If you have them, trends are the most helpful thing we look at in determining your engine’s health. It takes three samples to get a good trend going (though we can often tell if something is amiss earlier than that).

If you have them, trends are the most helpful thing we look at in determining your engine’s health. It takes three samples to get a good trend going (though we can often tell if something is amiss earlier than that).

All engines are different, as are their drivers, how they’re used, and where they are in the country. As such, it’s very helpful to sample a few oil changes in a row, at least at first, and have a baseline established for your specific engine. Consistency counts. If your engine is wearing a lot but it’s doing so steadily, it’s possible that the metal isn’t a problem. Problems tend to get worse over time – not remain stagnant.

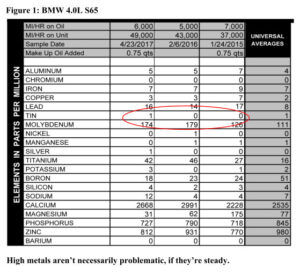

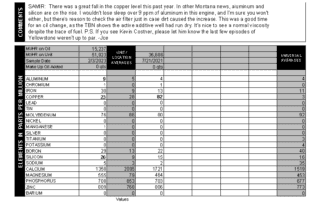

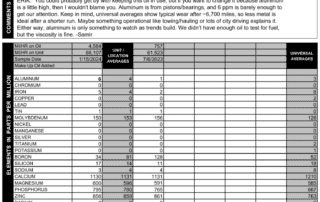

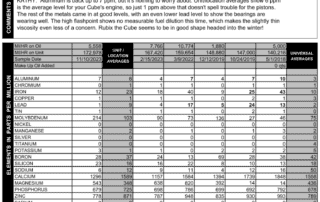

Figure 1 is a good example where lead (a bearing metal) doesn’t appear to be a problem. That engine has more lead than average, but it’s consistent. Since the owner wasn’t having any problems, our recommendation was to just watch lead as time goes on.

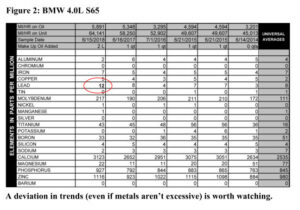

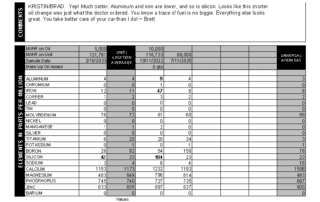

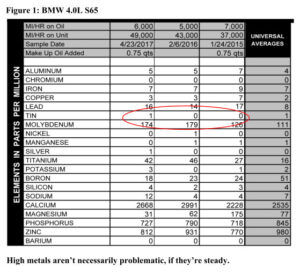

But on the other hand, look at Figure 2. Lead read at just 12 ppm in this sample—that’s well within the average range, but we marked it because lead had always been much lower than this. If this had been his first report, we might have thought lead was okay. But since we know that lead is usually low, we told him the bearings are wearing more than they were and to watch for abnormalities like low oil pressure.

Universal averages

Of course, when you start sampling, you don’t have trends to rely on. So our second line of defense, when we’re looking at your numbers, is universal averages.

We have averages established for most of the engines out there, though we’re always adding to our database as new types of engines (and transmissions and generators and other machinery) are being made all the time. When you do your first sample, we’ll compare your metals to averages for your specific engine.

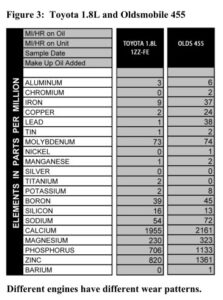

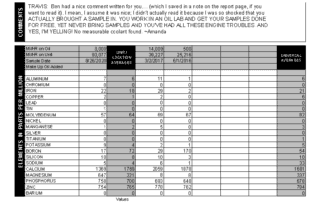

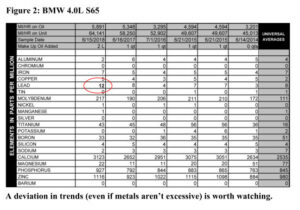

It’s helpful for us to know what kind of engine you have. Look at Figure 3, for example. This is a comparison between the Toyota 1.8L 1ZZ-FE (used in Corollas and Vibes), and the Oldsmobile 455 (used in older motorhomes and the Cutlass and Trans Am). Toyotas don’t wear much, whereas the Olds 455 makes a lot of metal.

If we don’t know what kind of engine you have, we might end up comparing your numbers to the wrong set of averages, or just a generic engine file. We can still tell if something is way out of line, but the more subtle differences between your engine and averages are harder to see.

If we don’t know what kind of engine you have, we might end up comparing your numbers to the wrong set of averages, or just a generic engine file. We can still tell if something is way out of line, but the more subtle differences between your engine and averages are harder to see.

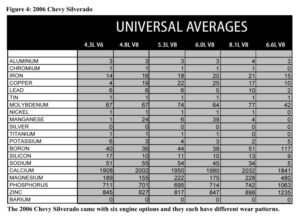

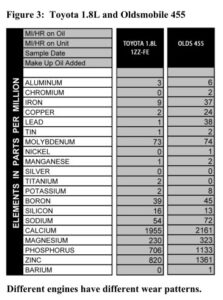

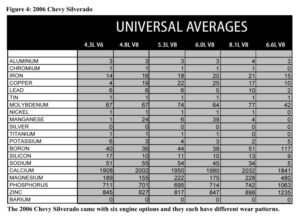

Along those same lines, some vehicles come with many different engine options, so just telling us the year, make, and model of your vehicle isn’t always enough. The 2006 Silverado, for example, could have one of five different gas engines or the 6.6L diesel engine in it. We have different averages for each of those engine types. Take a look at Figure 4. The metals are similar in those engines, but they’re different enough to matter when we’re determining if something is too high or not.

Generally speaking, we’ll mark a metal in bold when it’s twice average or more. But not always—there are also times when we don’t mark elevated metals, if we know something else is going on.

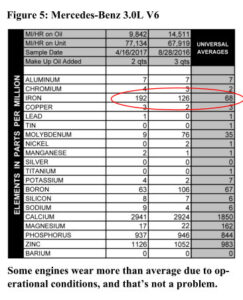

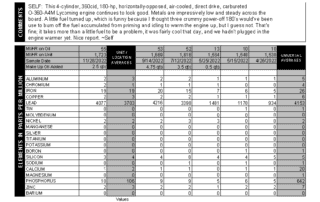

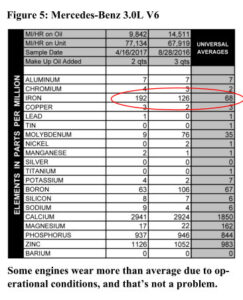

We test a fleet of armored Sprinter vans that operate in New York City, for example. The vehicles are loaded up with armor and spend their entire lives idling and driving in unforgiving traffic conditions. It’s no surprise that the engines wear more than average. (See Figure 5.)

Balance of metals

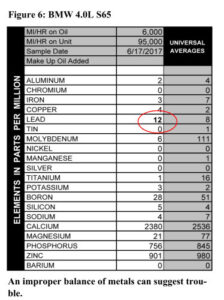

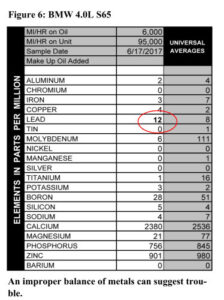

We also look at the balance of metals relative to each other. In Figure 6, lead is not reading twice average but we marked it anyway. According to averages, lead and iron should be at about a 1:1 ratio. In this sample, the lead: iron ratio is more like 4:1. This balance tells us the bearings are wearing more than the rest of the engine, and that can be a sign of trouble too.

Additives

Another factor to consider is the use of additives and/or leaded fuel. Lots of people use Restore, which has copper and lead in it, and although in that form those elements aren’t harmful, they do make your numbers read high.

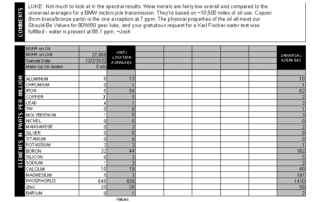

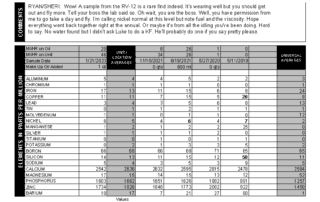

Likewise, if you’re using leaded fuel, racing fuel or certain octane boosters, fuel blow-by will cause high lead readings. The highest lead reading we’ve seen in any BMW S65 engine was 1055 ppm. The rest of the metals looked great, though, and the customer had mentioned using an additive, so we were pretty sure the lead in his sample wasn’t a sign of an impending bearing failure.

How much metal is too much?

So how much metal is too much? In truth that number is different for every engine. You already know that we take a lot of things into account in trying to answer that question. Usually we’ll call you to get more information if we’re not sure, and we’ll suggest giving it an oil change or two to see how trends shake out. If something is seriously out of line we can usually tell, even if we don’t know your engine type or how you use it.

We will say this, though: it’s pretty rare for a major mechanical problem to happen unexpectedly overnight. Most engines will give at least some warning before things go south, and that’s why you do analysis. Follow the trends to see what’s normal for your engine, and when deviations occur, you’re informed enough to make a good decision.

If you have them, trends are the most helpful thing we look at in determining your engine’s health. It takes three samples to get a good trend going (though we can often tell if something is amiss earlier than that).

If you have them, trends are the most helpful thing we look at in determining your engine’s health. It takes three samples to get a good trend going (though we can often tell if something is amiss earlier than that).

If we don’t know what kind of engine you have, we might end up comparing your numbers to the wrong set of averages, or just a generic engine file. We can still tell if something is way out of line, but the more subtle differences between your engine and averages are harder to see.

If we don’t know what kind of engine you have, we might end up comparing your numbers to the wrong set of averages, or just a generic engine file. We can still tell if something is way out of line, but the more subtle differences between your engine and averages are harder to see.

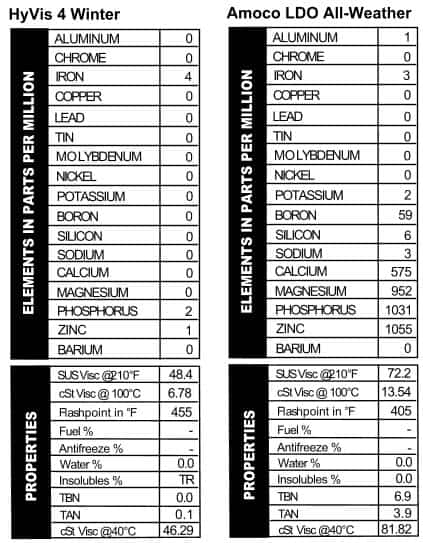

HyVis 4 Winter

HyVis 4 Winter additive in it, just not any that we read. The grade is not listed on the can, but the viscosity came back as a light 20W. With the lack of additive it’s not surprising that the TBN read 0.0. It’s tempting to do an experiment and run this apparent mineral oil for 10,000 miles in the dead of winter, just to see what would happen. If you know of any guinea pigs, send them our way!

additive in it, just not any that we read. The grade is not listed on the can, but the viscosity came back as a light 20W. With the lack of additive it’s not surprising that the TBN read 0.0. It’s tempting to do an experiment and run this apparent mineral oil for 10,000 miles in the dead of winter, just to see what would happen. If you know of any guinea pigs, send them our way! the country, and I’ll always associate the blue, red, and white logo with long trips across the country in our green van with the velour bed and hanging beads. But Amoco did more than fill up gas tanks in the 70s–they also sold oil, and this “Long Distance” version is an SAE 10W/40. The additive package looks a lot like the Mobil Special oil we saw: heavy on phosphorus and zinc, lighter on calcium and magnesium (Figure 2). Just the right oil for a couple of bandana-wearing hippies traveling with two little kids from Indiana to Nova Scotia in 1976 in a green van with a sunset painted on the side. Ah, the ’70s.

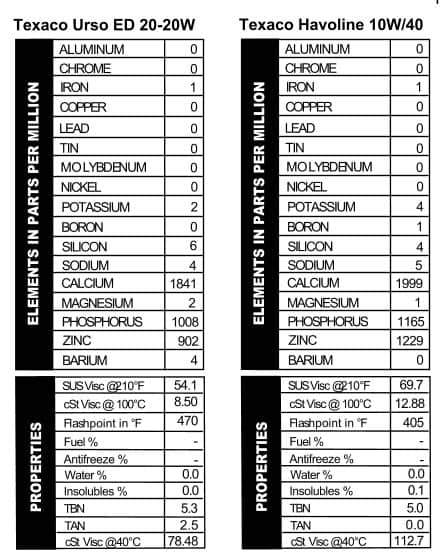

the country, and I’ll always associate the blue, red, and white logo with long trips across the country in our green van with the velour bed and hanging beads. But Amoco did more than fill up gas tanks in the 70s–they also sold oil, and this “Long Distance” version is an SAE 10W/40. The additive package looks a lot like the Mobil Special oil we saw: heavy on phosphorus and zinc, lighter on calcium and magnesium (Figure 2). Just the right oil for a couple of bandana-wearing hippies traveling with two little kids from Indiana to Nova Scotia in 1976 in a green van with a sunset painted on the side. Ah, the ’70s. The viscosity read like what we see today out of a standard 5W/30. Texaco Havoline Super Premium 10W/40, on the other hand, looks a lot like one of today’s diesel-use oils in additives (Figure 4), with a normal 10W/40 viscosity.

The viscosity read like what we see today out of a standard 5W/30. Texaco Havoline Super Premium 10W/40, on the other hand, looks a lot like one of today’s diesel-use oils in additives (Figure 4), with a normal 10W/40 viscosity.

only did they not make multi-viscosity oils that long ago, but the can comes from zip code 90017 so it has to be from 1963 or later. According to the can, it’s 100% parrafinic oil with selected additives, which our spectrometer reveals to be your standard line-up of calcium, phosphorus, and zinc (Figure 6). Look at that viscosity though¾it’s higher than we see in today’s 20W/50s.

only did they not make multi-viscosity oils that long ago, but the can comes from zip code 90017 so it has to be from 1963 or later. According to the can, it’s 100% parrafinic oil with selected additives, which our spectrometer reveals to be your standard line-up of calcium, phosphorus, and zinc (Figure 6). Look at that viscosity though¾it’s higher than we see in today’s 20W/50s.

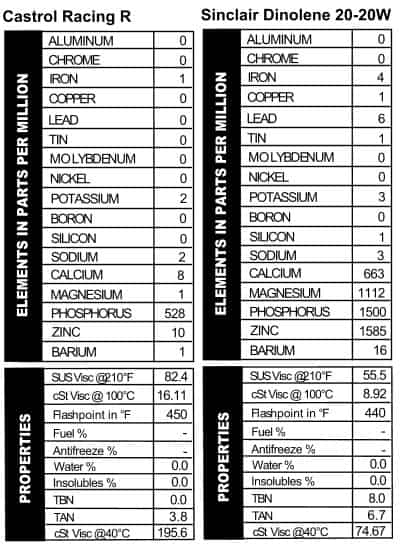

Like modern oils, they stress the high quality of the oil with terms like “organo-metallic” that are meant impress those of us who aren’t in the oil business. I don’t know if I’d call this a masterpiece in oil work though: it looks like what we see out of ATFs these days as far as additives go (mostly phosphorus with a little zinc thrown in). Since the word “Racing” is stamped into the top of the can, the thick viscosity (like a 50W) makes sense (Figure 7).

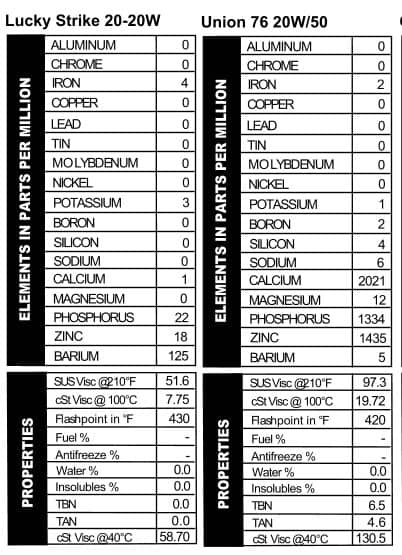

Like modern oils, they stress the high quality of the oil with terms like “organo-metallic” that are meant impress those of us who aren’t in the oil business. I don’t know if I’d call this a masterpiece in oil work though: it looks like what we see out of ATFs these days as far as additives go (mostly phosphorus with a little zinc thrown in). Since the word “Racing” is stamped into the top of the can, the thick viscosity (like a 50W) makes sense (Figure 7). I’ve always had a soft spot in my heart for Sinclair. The can has a picture of a dinosaur on it! This shit came from the ground, no doubt about it! Another 20-20W oil, the oil is light on advertising copy but heavy on additives. In fact, it looks a lot like recent versions of Shell’s Rotella 5W/40, except with a little less calcium. It’s much lighter than Shell’s 5W/40, though, with a viscosity reading like a 30W or a heavy 20W oil. Note the presence of lead (Figure 8).

I’ve always had a soft spot in my heart for Sinclair. The can has a picture of a dinosaur on it! This shit came from the ground, no doubt about it! Another 20-20W oil, the oil is light on advertising copy but heavy on additives. In fact, it looks a lot like recent versions of Shell’s Rotella 5W/40, except with a little less calcium. It’s much lighter than Shell’s 5W/40, though, with a viscosity reading like a 30W or a heavy 20W oil. Note the presence of lead (Figure 8).

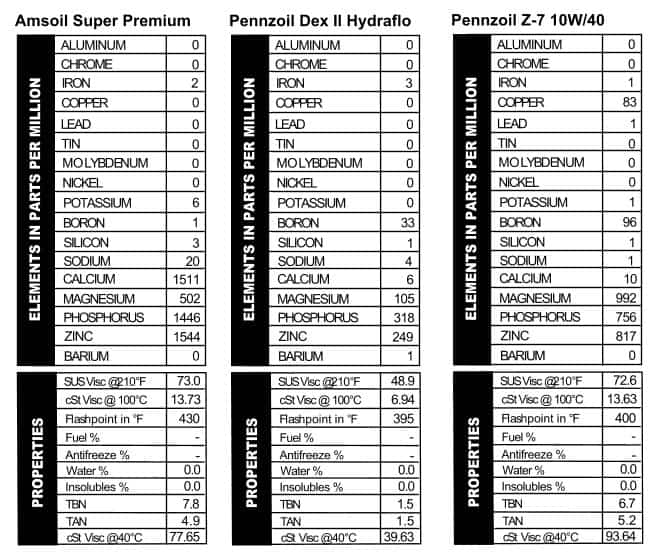

Modern Amsoil products tend to be heavy on additives and that was true back in the day as well (Figure 9). Just for fun, we compared this oil with a virgin sample of Amsoil 10W/40 that we ran in February 2012 and they look a lot alike. The only difference is in the older oil there’s less of everything: 500 ppm less calcium, and 100-200 ppm less phosphorus and zinc. They used magnesium in the older oil, while the TBN and viscosities were nearly identical.

Modern Amsoil products tend to be heavy on additives and that was true back in the day as well (Figure 9). Just for fun, we compared this oil with a virgin sample of Amsoil 10W/40 that we ran in February 2012 and they look a lot alike. The only difference is in the older oil there’s less of everything: 500 ppm less calcium, and 100-200 ppm less phosphorus and zinc. They used magnesium in the older oil, while the TBN and viscosities were nearly identical. over these two old cans. Originally, Penn’s Oil came from an oil field in Pennsylvania and was christened with a Liberty Bell logo to remind users of its Pennsylvania roots. This can of ATF clearly has an earlier generation of logo on it, and Google informs me that Dexron II was introduced in 1972. This may very well have been the transmission oil that kept our green van chugging through the ’70s. There are a lot of different ATFs in stores today, though generally they have about the same additive configurations. This one is a little different in that it has more boron, magnesium, and zinc than most modern ATFs. The viscosity is right where we’d expect it to be though. Pennzoil’s 10W/40 oil can is flashy, a la the

over these two old cans. Originally, Penn’s Oil came from an oil field in Pennsylvania and was christened with a Liberty Bell logo to remind users of its Pennsylvania roots. This can of ATF clearly has an earlier generation of logo on it, and Google informs me that Dexron II was introduced in 1972. This may very well have been the transmission oil that kept our green van chugging through the ’70s. There are a lot of different ATFs in stores today, though generally they have about the same additive configurations. This one is a little different in that it has more boron, magnesium, and zinc than most modern ATFs. The viscosity is right where we’d expect it to be though. Pennzoil’s 10W/40 oil can is flashy, a la the  1980s. It’s “The Motor Oil With Z-7” and although they don’t specify what that is, they do specify that “You need no extra oil additive.” So that’s reassuring. It’s rated SF-SC-CC, so I’d place it at about 25 years old. Maybe the magic of Z-7 is copper: that’s something we saw a lot of back in the day, when Blackstone was founded. Interestingly, magnesium is the dominant additive in this one, followed by zinc, phosphorus, copper, and boron (Figure 10). The flashpoint was lower than what we see today from 10W/40s.

1980s. It’s “The Motor Oil With Z-7” and although they don’t specify what that is, they do specify that “You need no extra oil additive.” So that’s reassuring. It’s rated SF-SC-CC, so I’d place it at about 25 years old. Maybe the magic of Z-7 is copper: that’s something we saw a lot of back in the day, when Blackstone was founded. Interestingly, magnesium is the dominant additive in this one, followed by zinc, phosphorus, copper, and boron (Figure 10). The flashpoint was lower than what we see today from 10W/40s.

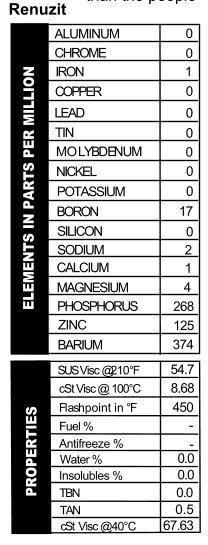

a can like the others. This one was sold in a 5-quart metal jug. I particularly love this one, because the can not only says you’ll “Cut Your Oil Bills In Half,” but the first point of advertising on the side is a “Faster Getaway!” Now, they don’t actually say that this is the choice of oils for bank robbers, but I know if it was 1941 and my hungry Great Depression self was contemplating which oil to put in my Ford Special for bank-robbing time, this is the oil I’d pick. With practically no calcium or magnesium present, the oil’s TBN read 0.0, but it does provide would-be crooks with phosphorus, zinc, and barium as well as a 20W viscosity for the getaway (Figure 11). When you’re busy working a tommy gun, the last think you want to think about is whether or not you’ve made the right choice in oil.

a can like the others. This one was sold in a 5-quart metal jug. I particularly love this one, because the can not only says you’ll “Cut Your Oil Bills In Half,” but the first point of advertising on the side is a “Faster Getaway!” Now, they don’t actually say that this is the choice of oils for bank robbers, but I know if it was 1941 and my hungry Great Depression self was contemplating which oil to put in my Ford Special for bank-robbing time, this is the oil I’d pick. With practically no calcium or magnesium present, the oil’s TBN read 0.0, but it does provide would-be crooks with phosphorus, zinc, and barium as well as a 20W viscosity for the getaway (Figure 11). When you’re busy working a tommy gun, the last think you want to think about is whether or not you’ve made the right choice in oil.