How Often Should I Sample?

One of the most common questions we get asked is, “How often should I send in a sample?” and this is one that I tend to struggle with answering.

The businessman in me says at every oil change regardless, and while you’re at it, check your transmission fluid, differential fluid, and your wife’s/husband’s car. And don’t forget any air compressors, lawn mowers, wood splitters, etc. you may own. And your neighbor’s car was smoking a bit last time you saw it drive past, better check that too.

Unfortunately, before I start talking, my “realist” side kicks in and I usually say something like once a year, after you have some good trends established. But even that answer doesn’t always apply. What if you don’t drive your vehicle very often, or at all? Is it really necessary to test the oil once a year? The answer to that is once again not really. Though if you think you might have a problem developing, then it could be a good idea to sample more often than you normally would.

Old oil

We recently had a customer send in a sample of oil that was in an engine for 10 years and had not been run at all in more than 5 years — and amazingly enough wear metals were virtually identical to what we were seeing when he last sampled 10 years ago.

The only significant difference was at insolubles. These had gone from 0.2% to 0.0% after the 5 years of sitting. We figured the reason for this was gravity. All normal engine oils contain dispersant additives, and their function is to hold dirt and solids in suspension so they can be filtered out. Do they work? Absolutely, but asking them to work for a full five years is a little much. The good news is that the additives are still in the oil, so once the engine starts up and sees some use, those solids should be picked up and dispersed again.

So, if we can say with good certainty that the oil itself won’t go bad just sitting in an engine, you might wonder why it needs to be changed at all? The answer to that is contamination.

Contamination problems

Engine oil has maybe the hardest life of any oil application out there. Not only does it see frequent temperature swings of 150° to 200°F (65° to 90°C), but it will also get contaminated with fuel blow-by and a little atmospheric water as well.

Ideally the fuel and water will boil out once the oil gets up to operating temperature, but that contamination will add up over time and eventually cause the oil to start to oxidize. If you can pinpoint exactly when the oil will oxidize enough that it will start to affect wear or cause the oil’s viscosity to change, that’s the point at which you want to change the oil. If you test your oil on a regular basis, you can start to identify that point and that’s one of the reasons why we’re here.

So when is the best time to get a sample? The answer to that is: it depends.

Best time to sample?

If you just bought a brand-new car, the first oil is factory oil and while that oil will sometimes have an unusual additive package, it’s not that useful for finding a problem, or developing a normal wear trend.

Factory oil is typically loaded with excess metal from wear-in of new parts as well and some silicon from sealers used when the engine was assembled, and this stuff normally takes two or three oil changes to wash out.

So, while these samples aren’t useful as far as trends go, they are useful in finding problems in engines that have been recently rebuilt or had other major work done, and we always recommend testing those from the beginning. This is because if wear metals don’t drop from that initial oil fill, it can be the early indication of a problem.

It’s always a good idea to get a trend going while the engine is running well. A trend consists of three samples. Once we have that established and the engine is running perfectly, then it’s not really necessary to get a sample at each oil change and at that point it’s okay in most cases to go to a once-a-year sampling routine.

Once a year?

You might be wondering why once a year? The reason for that is two-fold. One: A lot of people (including myself) only change their oil once a year. It’s also the only time I crawl under my car and have the hood open. I consider it like an annual inspection and there are been numerous times that I have been on my back waiting for the oil to drain when I noticed another problem like a seeping freeze-plug or a torn CV boot. Two: It’s easy to remember.

However, the once-a-year rule doesn’t always apply. There are many vehicles out there that only see light use (maybe less than 500 miles a year), so not only can they typically skip changing oil on a yearly basis, then don’t need to sample every year.

Another factor is how important the vehicle is to you. If you rely on it for your business, or it’s the only vehicle you have and it’s getting up there in mileage, then sampling at every oil change might be a very good idea.

Engines speak before they fail

We can see problems developing in your engine long before they actually cause a failure, so you normally have some time to do something about any trouble we might spot. Still, like a lot of things in life, the earlier you know about problems the better.

We get as lot of samples from engines that have a known problem, so we test the oil and usually see poor wear, but telling how bad the problem is or how/when it started is hard without trends from when the engine was normal. We do have averages that give us a good idea how an engine should look overall, but they aren’t as valuable as trends when it comes to saying exactly what’s normal for a particular engine and the use it sees.

So there you have it, I’m actually saying you may not need our services as much as you might think. Some of the other business owners out there might call me crazy and I guess they’re right. But please, feel free to sample anytime you like. As you know there is nothing better than getting a glowing oil report on your pride and joy.

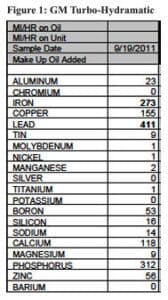

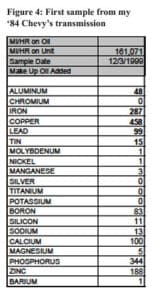

It was always a bit of a mystery as to where lead came from in that type of transmission and it turns out, it’s a bearing metal, just like what used to be common in engines.

It was always a bit of a mystery as to where lead came from in that type of transmission and it turns out, it’s a bearing metal, just like what used to be common in engines.

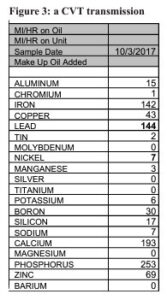

Again, most of these oils are light in viscosity (10W) but they have a unique additive package, and they also tend to be dyed blue or green to differentiate them from the typical red ATF that many transmissions run. Unfortunately, we see a lot of samples from CVT transmissions where the wrong oil has been used. This causes the units to burn up because the belt driving the cones relies on the oil’s additives to maintain the correct friction.

Again, most of these oils are light in viscosity (10W) but they have a unique additive package, and they also tend to be dyed blue or green to differentiate them from the typical red ATF that many transmissions run. Unfortunately, we see a lot of samples from CVT transmissions where the wrong oil has been used. This causes the units to burn up because the belt driving the cones relies on the oil’s additives to maintain the correct friction.

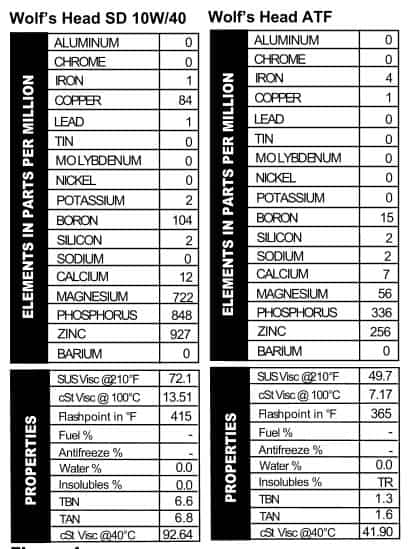

Wolf’s Head SD 10W/40

Wolf’s Head SD 10W/40 Wolf’s Head ATF

Wolf’s Head ATF white, and blue, so you can feel patriotic when you buy it (unless

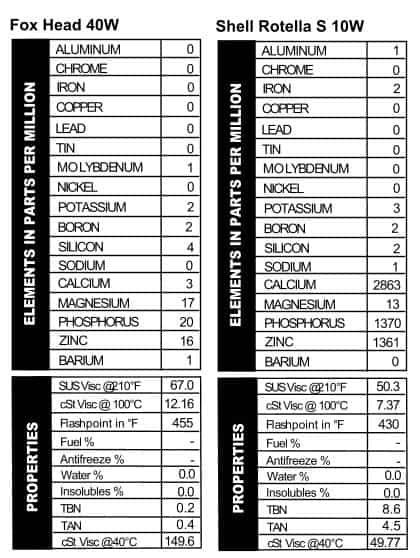

white, and blue, so you can feel patriotic when you buy it (unless  you’re in Canada. Then you can indulge in justified rage about Americans and how we think we’re the center of the world). Fox Head oil was made by the Tritex Petroleum company out of Brooklyn, NY, and my extensive research (aka first-page Google results) tells me the company still exists and is presently located in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The logo, a sly-looking fox, has nothing on today’s slick oil packages. And the oil itself also has nothing on today’s oils: the oil itself is nearly bereft of additives. Basically a mineral oil, it has a little magnesium, phosphorus, and zinc in it, and not a lot else (Figure 3). This is not necessarily a problem, however. As you’ll recall in the article when Ryan used 30W aircraft oil in his truck, wear went up a little but the engine didn’t fail or anything. Still, I won’t be putting it in my Outback anytime soon.

you’re in Canada. Then you can indulge in justified rage about Americans and how we think we’re the center of the world). Fox Head oil was made by the Tritex Petroleum company out of Brooklyn, NY, and my extensive research (aka first-page Google results) tells me the company still exists and is presently located in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The logo, a sly-looking fox, has nothing on today’s slick oil packages. And the oil itself also has nothing on today’s oils: the oil itself is nearly bereft of additives. Basically a mineral oil, it has a little magnesium, phosphorus, and zinc in it, and not a lot else (Figure 3). This is not necessarily a problem, however. As you’ll recall in the article when Ryan used 30W aircraft oil in his truck, wear went up a little but the engine didn’t fail or anything. Still, I won’t be putting it in my Outback anytime soon. long they’ve been making this oil and the guy not only could not tell me, but he was unable to tell me who might know. Surely someone at that company has a historical file? If so, they’re not sharing that info with plebeians like us. He did mention that Rotella really made its name in the ’70s, though I’m guessing this can of SF, SE, SC oil was made in the late ’80s. He also said the “S” versions of Rotella were sold internationally, and indeed, this can came from our friendly neighbors to the north (*waves hi to Canada). Suffice it to say that the oil has changed very little over the years. Its main additives are the same as what we see today, but the interesting part of this oil is that it’s a 10W (Figure 4). We often see heavy-duty thin-grade additive packages in tractor-hydraulic fluids, which are used in systems like transmissions and hydraulic systems in off-highway equipment like bulldozers and backhoes. Note the TBN of this oil read higher than most of the others we’re talking about. That’s because of the high calcium level¾the TBN is based on the level of calcium sulfinate and/or magnesium sulfinate. When those compounds aren’t present, you get a low TBN.

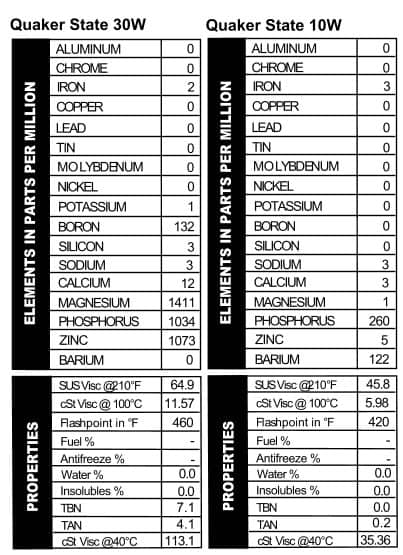

long they’ve been making this oil and the guy not only could not tell me, but he was unable to tell me who might know. Surely someone at that company has a historical file? If so, they’re not sharing that info with plebeians like us. He did mention that Rotella really made its name in the ’70s, though I’m guessing this can of SF, SE, SC oil was made in the late ’80s. He also said the “S” versions of Rotella were sold internationally, and indeed, this can came from our friendly neighbors to the north (*waves hi to Canada). Suffice it to say that the oil has changed very little over the years. Its main additives are the same as what we see today, but the interesting part of this oil is that it’s a 10W (Figure 4). We often see heavy-duty thin-grade additive packages in tractor-hydraulic fluids, which are used in systems like transmissions and hydraulic systems in off-highway equipment like bulldozers and backhoes. Note the TBN of this oil read higher than most of the others we’re talking about. That’s because of the high calcium level¾the TBN is based on the level of calcium sulfinate and/or magnesium sulfinate. When those compounds aren’t present, you get a low TBN. Quaker State 30W & 10W

Quaker State 30W & 10W

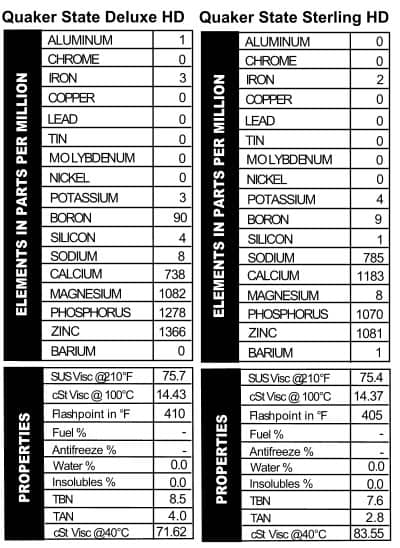

these oils are mostly the same; they’ll throw in a few slight differences in additives and call it good. These cans of Quaker State, however, were mostly pretty different. The Deluxe version looked a lot like their 30W oil (but more calcium–Figure 7). Quaker State Sterling HD 10W/40, on the other hand, went out on a limb with almost 800 ppm sodium, almost no magnesium, and then levels of calcium, phosphorus, and zinc that are comparable with today’s oils. Touted as “Energy Saving Motor Oil,” Quaker State was getting its game on in pushing this brand: it mentions “special friction modifying additives,” the longevity of the company (over 60 years when the can was made), and its suitability for those wishing to follow extended drain intervals. Heck, I’m sold, and I see this stuff all the time.

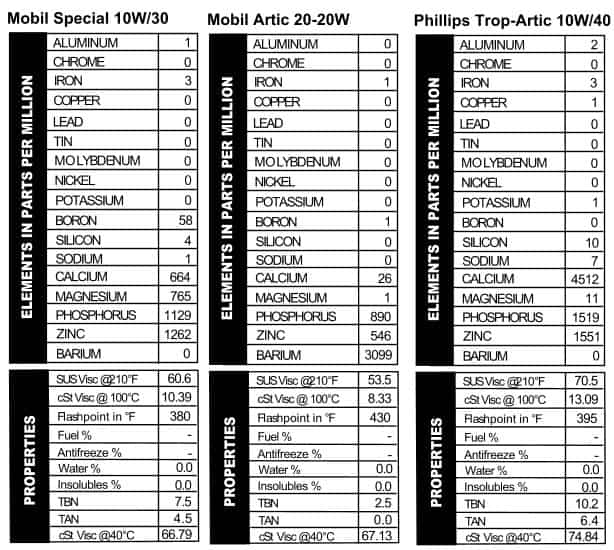

these oils are mostly the same; they’ll throw in a few slight differences in additives and call it good. These cans of Quaker State, however, were mostly pretty different. The Deluxe version looked a lot like their 30W oil (but more calcium–Figure 7). Quaker State Sterling HD 10W/40, on the other hand, went out on a limb with almost 800 ppm sodium, almost no magnesium, and then levels of calcium, phosphorus, and zinc that are comparable with today’s oils. Touted as “Energy Saving Motor Oil,” Quaker State was getting its game on in pushing this brand: it mentions “special friction modifying additives,” the longevity of the company (over 60 years when the can was made), and its suitability for those wishing to follow extended drain intervals. Heck, I’m sold, and I see this stuff all the time. Mobil is no slouch in the marketing department, but they really outdid themselves with the can we tested, “Mobil Special.” The name alone tells you all you need to know about why to buy this oil. All oil companies like to mess with their additive packages, and Mobil, like the others, changes their oil up fairly frequently. That was the case back in the day too, because the additive package in this “Special” oil is different from what we typically see in today’s oil. Apparently Mobil was an early rider on the ZDDP train, because this oil is chock-full of both phosphorus and zinc. Calcium and magnesium are present too, but at lower levels (Figure 8). We also tested a sample of Mobil Artic oil. The Artic

Mobil is no slouch in the marketing department, but they really outdid themselves with the can we tested, “Mobil Special.” The name alone tells you all you need to know about why to buy this oil. All oil companies like to mess with their additive packages, and Mobil, like the others, changes their oil up fairly frequently. That was the case back in the day too, because the additive package in this “Special” oil is different from what we typically see in today’s oil. Apparently Mobil was an early rider on the ZDDP train, because this oil is chock-full of both phosphorus and zinc. Calcium and magnesium are present too, but at lower levels (Figure 8). We also tested a sample of Mobil Artic oil. The Artic can is clearly older than the other Mobil can¾the logo is older, and there’s no zip code listed with the address, so it’s pre-1963. A straight 20W, it’s labeled as HD oil, meeting “Car Builders’ Most Severe Service Tests.” While it’s “Artic” and not “Arctic,” we can’t help thinking this oil is meant for cold-weather operation. The can even looks like it’s ready for winter: all white, but with a little color on it so you don’t lose it in the snow when you’re out in the tundra changing your oil. This one definitely has an unusual additive package, relying heavily on barium (maybe it’s got a purpose after all!). Interestingly, less zinc is present than phosphorus (Figure 9). Nowadays it’s the other way around.

can is clearly older than the other Mobil can¾the logo is older, and there’s no zip code listed with the address, so it’s pre-1963. A straight 20W, it’s labeled as HD oil, meeting “Car Builders’ Most Severe Service Tests.” While it’s “Artic” and not “Arctic,” we can’t help thinking this oil is meant for cold-weather operation. The can even looks like it’s ready for winter: all white, but with a little color on it so you don’t lose it in the snow when you’re out in the tundra changing your oil. This one definitely has an unusual additive package, relying heavily on barium (maybe it’s got a purpose after all!). Interestingly, less zinc is present than phosphorus (Figure 9). Nowadays it’s the other way around. see out of modern 15W/40s¾a stout additive package and a relatively thick viscosity (Figure 10). In other words, even though this oil is several decades old, it would be fine to use in your F150 tomorrow.

see out of modern 15W/40s¾a stout additive package and a relatively thick viscosity (Figure 10). In other words, even though this oil is several decades old, it would be fine to use in your F150 tomorrow.

and needed some oil for my Passat. It just starting to clatter a little on start up and when I checked the oil, it was down two quarts. The clatter sounded something like “Sell Me” in German.

and needed some oil for my Passat. It just starting to clatter a little on start up and when I checked the oil, it was down two quarts. The clatter sounded something like “Sell Me” in German.

One thing led to another and before I knew it I had bought 28 cans of old oil and spent almost $1,000. Pretty soon these oils started rolling in and I experienced a little buyers remorse. Did I really need to buy all this? What was I going to do with the cans? Once you open a can of oil, it’s almost impossible to seal up properly. Would there be anything to even see in these samples? And, does oil go bad? We get this last question all the time, and my answer has always been no, but I was dealing with oils from the 1930s,1940s, and 1950s here–really old stuff. Maybe all the additive in there (if any was even used) would settle out and there wouldn’t be anything for us to read. Fortunately, I had bought some oil that would help answer that.

One thing led to another and before I knew it I had bought 28 cans of old oil and spent almost $1,000. Pretty soon these oils started rolling in and I experienced a little buyers remorse. Did I really need to buy all this? What was I going to do with the cans? Once you open a can of oil, it’s almost impossible to seal up properly. Would there be anything to even see in these samples? And, does oil go bad? We get this last question all the time, and my answer has always been no, but I was dealing with oils from the 1930s,1940s, and 1950s here–really old stuff. Maybe all the additive in there (if any was even used) would settle out and there wouldn’t be anything for us to read. Fortunately, I had bought some oil that would help answer that.

However, that really didn’t get down to answering the question: Is this oil still good to use? For that, I was going to have to run another test.

However, that really didn’t get down to answering the question: Is this oil still good to use? For that, I was going to have to run another test. .

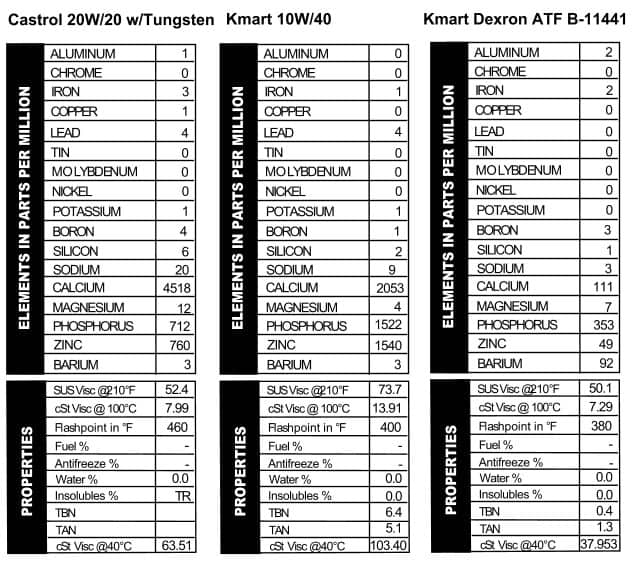

. Looking at the results, I’d say this oil is indeed deluxe. The viscosity is pretty strong for a 10W/40, and the additives would be suitable for diesel use. The oil does have a CC rating as well as an SE rating, and those put the date of this oil as being made sometime in the 1970s. The ATF has a standard additive package until you get down to barium. That’s not used much anymore. See figures 5 and 6 for the analyses.

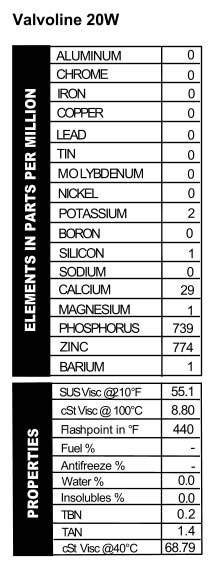

Looking at the results, I’d say this oil is indeed deluxe. The viscosity is pretty strong for a 10W/40, and the additives would be suitable for diesel use. The oil does have a CC rating as well as an SE rating, and those put the date of this oil as being made sometime in the 1970s. The ATF has a standard additive package until you get down to barium. That’s not used much anymore. See figures 5 and 6 for the analyses. Valvoline SAE 20W – API SB

Valvoline SAE 20W – API SB